MANIFESTO

Een manifest is een gepubliceerde mondelinge verklaring van de intenties, motieven, of uitzicht op de uitgevende instelling, of het nu een persoon, groep, politieke partij of de overheid.

Een manifest accepteert meestal een eerder gepubliceerde mening of publieke consensus en / of promoot een nieuw idee met normatieve begrippen voor het uitvoeren van de auteur is van mening verandert moet worden gemaakt. Het is vaak politieke of artistieke aard, maar kan een individu het leven houding te presenteren. Manifesten met betrekking tot religieuze overtuiging worden in het algemeen aangeduid als geloofsbelijdenissen.

MANIFESTO OF ARTISTS:

1IERE MANIFESTE DE LA REVUE D'ART "LE STYLE" [sic], published in 1918

The Futurist Manifesto (1909), by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

The Art of Noises (1913), by Luigi Russolo

The Dada Manifesto (1918), by Tristan Tzara

The Surrealist Manifesto (1924), by André Breton

The Symbolist Manifesto (1886), by Jean Moreas

The Free Cinema Manifesto (1956) by Lindsay Anderson Karel Reisz Tony Richardson Lorenza Mazzetti

Fluxus manifesto (1961) by George Maciunas

The Romantic Manifesto (1969) by Ayn Rand

Manifesto of Poetic Eggs, in "Empire of Dreams," (1998 in Spanish, 1994 in English) by Giannina Braschi

Dogma 95 (1995) by Lars von Trier, Thomas Vinterberg, Kristian Levring and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen

Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity[6] (1996) by Basarab Nicolescu

Minnesota declaration:[7] truth and fact in documentary cinema (1999), by Werner Herzog

First Things First 2000 manifesto:

Ethics and social responsibility in graphic design (1999)

The Versatilist manifesto (2007), by Denis Mandarino

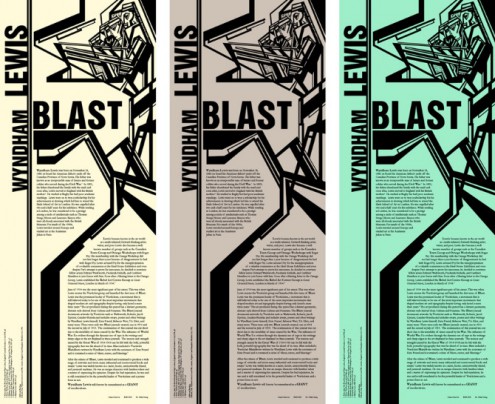

BLAST the Vorticist manifesto, by Wyndham Lewis

The Art of Noises

"Ancient life was all silence"

Russolo states that "noise" first came into existence as the result of 19th century machines. Before this time the world was a quiet, if not silent, place. With the exception of storms, waterfalls, and tectonic activity, the noise that did punctuate this silence were not loud, prolonged, or varied.

Early sounds

He notes that the earliest "music" was very simplistic and was created with very simple instruments, and that many early civilizations considered the secrets of music sacred and reserved it for rites and rituals. The Greek musical theory was based on the tetrachord mathematics of Pythagoras, which did not allow for any harmonies. Developments and modifications to the Greek musical system were made during the Middle Ages, which led to music like Gregorian chant. Russolo notes that during this time sounds were still narrowly seen as "unfolding in time. The chord did not yet exist.

"The complete sound"

Russolo refers to the chord as the "complete sound," the conception of various parts that make and are subordinate to the whole. He notes that chords developed gradually, first moving from the "consonant triad to the consistent and complicated dissonances that characterize contemporary music. He notes that while early music tried to create sweet and pure sounds, it progressively grew more and more complex, with musicians seeking to create new and more dissonant chords. This, he says, comes ever closer to the "noise-sound."

Musical noise

Russolo compares the evolution of music to the multiplication of machinery, pointing out that our once desolate sound environment has become increasingly filled with the noise of machines, encouraging musicians to create a more "complicated polyphony"[3] in order to provoke emotion and stir our sensibilities. He notes that music has been developing towards a more complicated polyphony by seeking greater variety in timbres and tone colors.

Noise-Sounds

Russolo explains how "musical sound is too limited in its variety of timbres." He breaks the timbres of an orchestra down into four basic categories: bowed instruments, metal winds, wood winds, and percussion. He says that we must "break out of this limited circle of sound and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds," and that technology would allow us to manipulate noises in ways that could not have been done with earlier instruments.

Future sounds

Russolo claims that music has reached a point that no longer has the power to excite or inspire. Even when it is new, he argues, it still sounds old and familiar, leaving the audience "waiting for the extraordinary sensation that never comes."[4] He urges musicians to explore the city with "ears more sensitive than eyes,"[ listening to the wide array of noises that are often taken for granted, yet (potentially) musical in nature. He feels these noises can be given pitch and "regulated harmonically," while still preserving their irregularity and character, even if it requires assigning multiple pitches to certain noises.

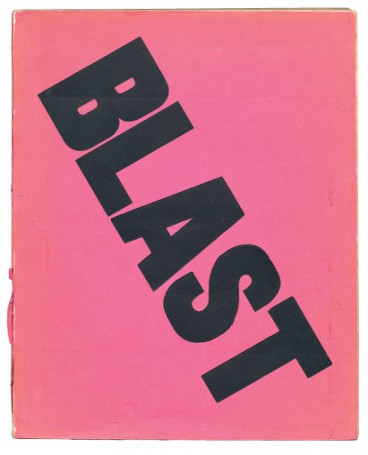

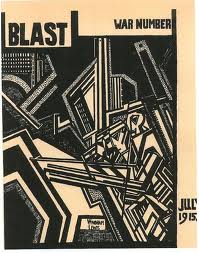

BLAST - MAGAZINE

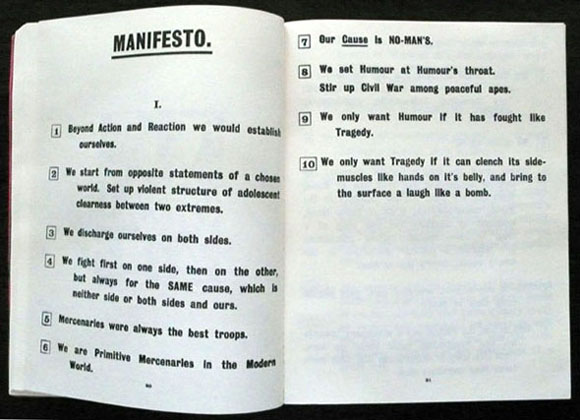

The Manifesto

The first section of Wyndham Lewis' Manifesto, Blast 1, 1914

The manifesto is primarily a long list of things to be 'Blessed' or 'Blasted'. It starts:

Beyond Action and Reaction we would establish ourselves.

We start from opposite statements of a chosen world. Set up violent structure of adolescent clearness between two extremes.

We discharge ourselves on both sides.

We fight first on one side, then on the other, but always for the SAME cause, which is neither side or both sides and ours.

Mercenaries were always the best troops.

We are primitive Mercenaries in the Modern World.

Our Cause is NO-MAN'S.

We set Humour at Humour's throat. Stir up Civil War among peaceful apes.

We only want Humour if it has fought like Tragedy.

We only want Tragedy if it can clench its side-muscles like hands on its belly, and bring to the surface a laugh like a bomb.

Refus global 1948

The Refus global (or Total Refusal) was an anti-establishment and anti-religious manifesto released on August 9, 1948 in Montreal by a group of sixteen young Québécois artists and intellectuals known as les Automatistes,

led by Paul-Émile Borduas.

The Refus global was greatly influenced by French poet André Breton, and it extolled the creative force of the subconscious.

Refus global 1948

The Refus global (or Total Refusal) was an anti-establishment and anti-religious manifesto released on August 9, 1948 in Montreal by a group of sixteen young Québécois artists and intellectuals known as les Automatistes,

led by Paul-Émile Borduas.

The Refus global was greatly influenced by French poet André Breton, and it extolled the creative force of the subconscious.

sol de witt manifesto

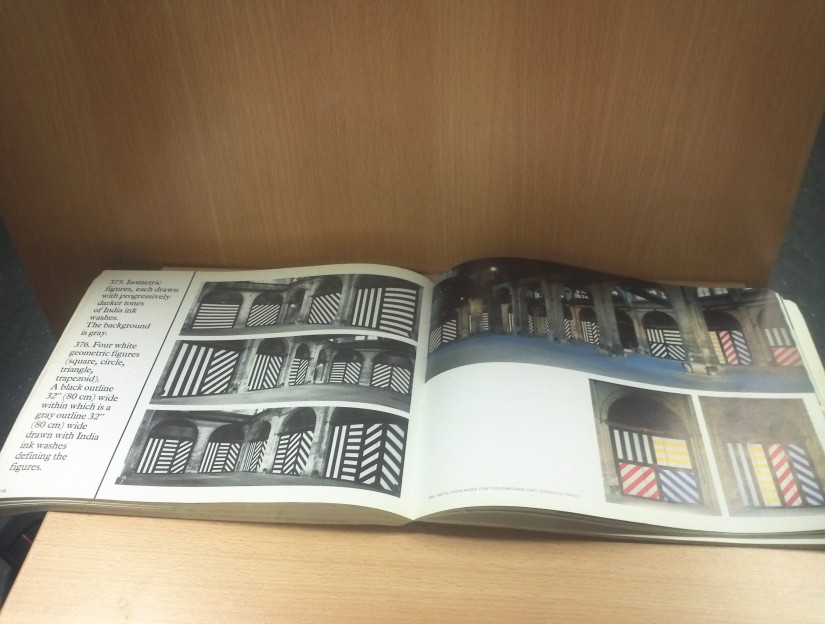

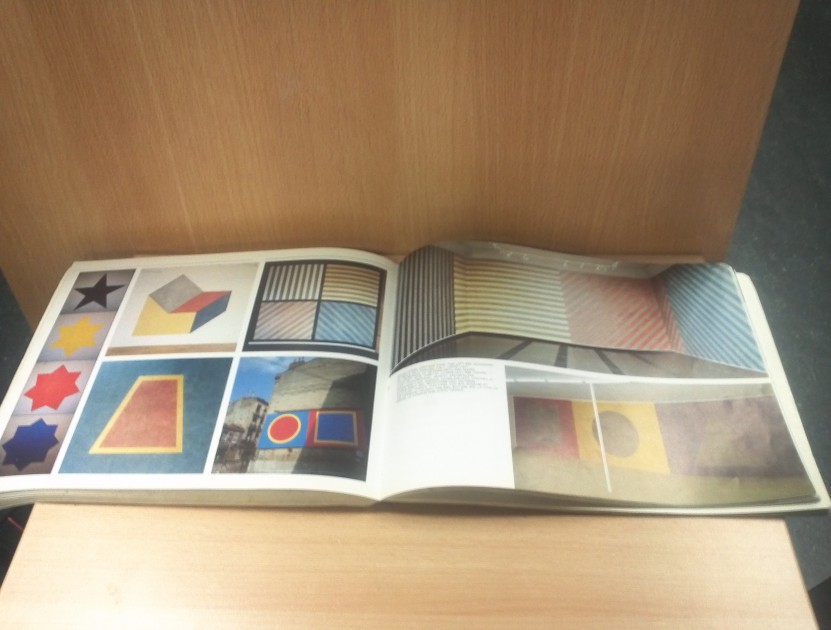

Sol Lewitt maakt ruimtelijke structuren, muur- en pentekeningen, foto's, grafiek en kunstenaarsboeken.

Sol Lewitt brak in het begin van de jaren 60 door met minimal art: ruimtelijke structuren die bestonden uit vierkanten en kubussen.

Hij ontwikkelde seriele systemen die waren gebaseerd op geometrische en wiskundige wetten die hij door een derde dimensie toe te voegen in minimalistische sculpturale structuren veranderde. Later bedacht hij muurschilderijen opgebouwd uit geometrische vormen.

Het vierkant is volgens hem de meest neutrale basisvorm om een concept zo objectief mogelijk gestalte te geven.

Om dezelfde reden maakt hij al vroeg gebruik van glad en wit materiaal.

Lewitt evolueerde door naar conceptuele kunst. Hij beschouwt zijn streng modulaire structuren, die bij de Minimal Art aansluiten, als serieel-conceptueel werk. De uitvoering liet hij aan anderen over. Conceptuele kunstwww.gemeentemuseum.nl)

Voor de Haagse Koninklijke Schouwburg ontwierp LeWitt opvallende kleurrijke fresco’s voor het interieur.

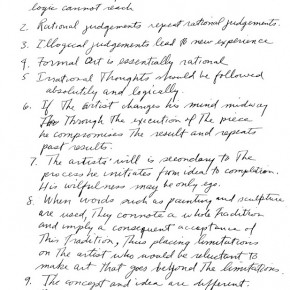

Sentences on Conceptual Art

by Sol Lewitt

Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.

Rational judgements repeat rational judgements.

Irrational judgements lead to new experience.

Formal art is essentially rational.

Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.

If the artist changes his mind midway through the execution of the piece he compromises the result and repeats past results.

The artist's will is secondary to the process he initiates from idea to completion. His wilfulness may only be ego.

When words such as painting and sculpture are used, they connote a whole tradition and imply a consequent acceptance of this tradition, thus placing limitations on the artist who would be reluctant to make art that goes beyond the limitations.

The concept and idea are different. The former implies a general direction while the latter is the component. Ideas implement the concept.

Ideas can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical.

Ideas do not necessarily proceed in logical order. They may set one off in unexpected directions, but an idea must necessarily be completed in the mind before the next one is formed.

For each work of art that becomes physical there are many variations that do not.

A work of art may be understood as a conductor from the artist's mind to the viewer's. But it may never reach the viewer, or it may never leave the artist's mind.

The words of one artist to another may induce an idea chain, if they share the same concept.

Since no form is intrinsically superior to another, the artist may use any form, from an expression of words (written or spoken) to physical reality, equally.

If words are used, and they proceed from ideas about art, then they are art and not literature; numbers are not mathematics.

All ideas are art if they are concerned with art and fall within the conventions of art.

One usually understands the art of the past by applying the convention of the present, thus misunderstanding the art of the past.

The conventions of art are altered by works of art.

Successful art changes our understanding of the conventions by altering our perceptions.

Perception of ideas leads to new ideas.

The artist cannot imagine his art, and cannot perceive it until it is complete.

The artist may misperceive (understand it differently from the artist) a work of art but still be set off in his own chain of thought by that misconstrual.

Perception is subjective.

The artist may not necessarily understand his own art. His perception is neither better nor worse than that of others.

An artist may perceive the art of others better than his own.

The concept of a work of art may involve the matter of the piece or the process in which it is made.

Once the idea of the piece is established in the artist's mind and the final form is decided, the process is carried out blindly. There are many side effects that the artist cannot imagine. These may be used as ideas for new works.

The process is mechanical and should not be tampered with. It should run its course.

There are many elements involved in a work of art. The most important are the most obvious.

If an artist uses the same form in a group of works, and changes the material, one would assume the artist's concept involved the material.

Banal ideas cannot be rescued by beautiful execution.

It is difficult to bungle a good idea.

When an artist learns his craft too well he makes slick art.

These sentences comment on art, but are not art.